Dernière mise à jour le 28 October 2025

Here’s a compilation of tips and useful things to know before visiting Japan, to get by more quickly and easily in this country with a language and culture very different from our own. If you still have some questions after reading this article (or if you’ve already visited Japan and can think of other useful info), leave me a comment to help me complete the article😊.

I’ve only been to Japan once, but I spent a whole month there, criss-crossing the country from Osaka to Hokkaido, visiting big cities as well as rural and mountain villages in different regions. In other words, I’ve seen just about every kind of bus and toilet you can imagine!

This article will focus on what you’ll experience on site, rather than on preparing for your trip (although some of these tips will help you a lot!). You can find my technique for organizing my trips on my own in another article, and see our detailed itinerary and travel logs in dedicated posts.

Note: Prices in € date from mid-2023 (1 yen = +/- 0.00675 €) and may vary according to current exchange rates.

Hi there! I’m a French-speaking writer and blogger and most of my content is in French. Please leave a comment to let me know if you enjoy my articles in English and would like me to continue translating my original posts!

Hi there! I’m a French-speaking writer and blogger and most of my content is in French. Please leave a comment to let me know if you enjoy my articles in English and would like me to continue translating my original posts!

Luggage

Packing light and washing clothes during the trip

You can travel light and not pack clothes for the entire duration of your trip: washing machines are available in all hotels as much as I could see.

They work with 100-yen coins only (you’ll need a lot of them, so remember to keep your change) and running a machine costs around 300 yen, or less than €2. Gentle drying generally costs 100 yen per 1/2 hour.

The product is added automatically and included in the price, so you don’t need to buy or bring detergent.

The washing machine area can get quite busy in the evening, so either plan a moment during the day to pass by the hotel and care for it, or check other public laundrettes in the area (the only time we used one, there was only one other patron).

Sending your luggage from one place to another

There’s a service that sends your luggage from one hotel to another, so you don’t have to take your luggage with you if you’re traveling by train or local plane between two cities. We used it twice and paid the equivalent of €30 per shipment for 2 large suitcases (between Kyoto and Nagano, and between Nagano and Sapporo).

This service is available at hotels and some stores (you can make purchases and send them directly to a hotel, or directly home). Just ask them about “ta-q-bin” or “kuro neko” (the company best known for this service) and they’ll know what you’re talking about!

Payment is always in cash. Prices vary according to the size of the luggage to be sent and the distance.

Luggage will be delivered the next day or two (probably a day or two longer if the distance to be covered is greater).

You can collect your luggage either at check-in or directly from your room. It’s always a good idea to let your destination hotel know that your luggage is on its way to them.

Coin lockers

Another tip to avoid walking around with your bags and luggage: coin lockers. You’ll find them in railway stations, at the entrance to most museums and attractions (often free of charge: you have to put in a 100 yen coin, but you get it back at the end) and in many other places.

They’re available for small bags, large suitcases and very large suitcases. The larger ones cost around 700/800 yen per 24 hours.

They are usually coin-operated (again, 100 yen each), but some can be paid for with an IC card (more on that card in the transport category below).

Transportation

What would Japan be without its incredible, efficient, clean, fast and always-on-time transportation? To plan your itineraries, I recommend using the official Japan Tourism application (potentially in combination with Google Maps).

Please note Japan is planning to change their system due to difficulty of maintaining this system and micro-chips supply shortage. They’d like to develop a system to pay directly with your phone or your contactless credit card (not yet active at the moment).

IC Card

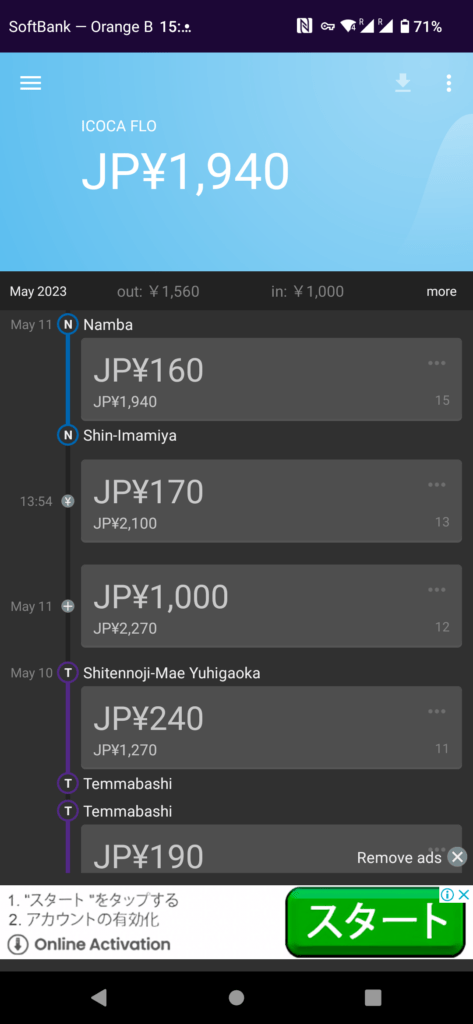

The IC card is a rechargeable transport card. It can be charged with any amount. All you have to do is beep when entering or exiting the transport system (rail doors, bus doors, etc.). Trips are slightly cheaper (a few yens) with the IC card.

IC Card mobile application

If you have an iPhone, you can have a virtual IC card on your phone (via Suica’s app, for example): you don’t then need to buy a physical card or reload at the machines (although you can), you can charge it with Apple Pay. You scan at the entrance to the transport system directly with your phone. At the time of writing, this feature is not yet available on Android phones which have not been manufactured for the Japanese market.

Kinds of IC cards

Depending on which region you buy it in, it’s supplied by ICoca, Pasmo, Suica…

There is a durable (hard) card that you can use for life, that comes in “registered” and “unregistered” version.

The “unregistered” card can be purchased very easily in several places, including automatic machines in stations. You can borrow one from someone you know who has been to Japan and still has theirs. However, if you’re traveling with several people, everyone must have their own! (WARNING: in June 2023, due to a shortage of electronic chips, the sale of non-nominative IC cards will be suspended. However, registered cards and temporary passes will still be sold, and it will still be possible to use the Apple application).

The “registered” card can only be bought at a JR office (to be checked, I’ve heard that some automatic machines also allow you to buy them), you have to fill in a form with your information, it can’t be lent, but if you lose it, you can have it re-issued, and it doesn’t cost more than the “unregistered” one.

There’s a deposit of 500 yen (€3.30). You can get 280 yen (€1.85) back if you return it (+ the money on it that hasn’t been spent). However, if you plan to return to Japan at a later date, be aware that the card is valid for 10 years from last use!

Finally, although all IC cards can be used and recharged anywhere in the country, they can only be returned in the region where they are issued (if you have a “Pasmo”, you can only return it to Pasmo, and Pasmo is in the Tokyo area. If you end your trip in Osaka, you won’t be able to return it there).

I advise you to buy it in Japan, as it’s almost free (apart from the 500 yen deposit), whereas buying it on the Internet from Europe can cost up to €20…

There are also temporary 28-day IC cards like the Pasmo Passport (which I haven’t used).

Other practical details regarding the IC cards

In some places, you can pay with your IC card at vending machines and coin lockers, as well as at konbinis (convenience store) and in some other stores and restaurants/snacks.

You can buy and recharge your IC card at machines in railway stations, where you can select the English language.

When you top up your IC card, you can do so with 10 yen (on the main screen, in the bottom right-hand corner, there’s a button for loading smaller currencies than the default 1000 yen). The machines generally work with cash.

If you don’t have enough credit on your IC card when you take the train, there are “Fare adjustment” machines inside the stations where you can top up your credit. However, you can avoid this kind of inconvenience by checking the price of the journey in advance on Google Maps (beware, the journey between point A and point B using two different train or metro lines can cost relatively more or less). There are unofficial applications for checking your credit from your phone (I personally used the Suikakeibo application on Android).

JR Pass

The JR Pass allows you to travel on a network of local, long-distance and fast trains (shinkansen or bullet train) throughout the country.

The official Japan Tourism application lets you simulate your journeys (in the manner of Google Maps) by indicating which tourist pass(es) you have, so you know which you’re entitled to with your pass at no extra charge.

It’s essential to order your pass in advance and pick it up at the office at the airport or at a JR station (this pass is only for foreign tourists). When you pick it up, you need to specify the date on which you want it to become active.

There is a pass that covers the whole country, and regional passes. Passes are valid for 7, 14 or 21 days.

The pass must be inserted into the portals at the station on entry and exit, so don’t forget to take it back each time (except in stations where someone checks it manually, see next point about stations)!

The pass does not guarantee access to trains: it is recommended to reserve your seat (most trains have reserved and non-reserved coaches, but some only have reserved coaches), which can be done at no extra charge at the automatic machines at the station (available in English). Your passport is needed to make a reservation with JR Pass.

The JR pass is not always worth it, so it’s best to do a simulation before you buy it (search for “JR pass simulator” on the Internet to find sites that let you do this, like this website).

In Tokyo, JR line codes are prefixed by a J (JK, JY…).

Stations

Most stations have automatic gates, but some smaller stations are “man-operated”: a member of staff will open access to the platform a few minutes before the train arrives and check your ticket to let you through (you can’t go onto the platforms until they’ve opened). This is the case in some stations with only 2 or 3 platforms.

In JR stations, there are stamps to collect. Sometimes you have to search a bit, but they’re usually available on a self-service basis (sometimes you have to ask the staff). They’re a great free souvenir to collect during your trip.

Shinkansen

The space in the Shinkansen is just insane, you can put a suitcase in front of your legs (although there are spaces at each end of the coach to put luggage).

If you have very large luggage (larger than the maximum allowed in the hold of an aircraft), you must reserve your seat on the Shinkansen. It’s free, but if you don’t, you risk paying a fine or not being able to make your journey.

When you have to get off the Shinkansen, be ready before the train stops. If Japanese are always on time, it’s because they’re super-efficient. This means, among other things, that the train stops at the station only 1 or 2 minutes, so there’s no time to gather your things when the doors are already open.

We don’t eat on trains, except on the Shinkansen. In fact, these are practically the only trains with trash cans on board.

When you enter the Shinkansen area, you’ll find stores selling eki-ben (“station bento”), which you can eat on board the Shinkansen. You’ll find them in the station concourse and on the platforms. Personally, I find them rather expensive compared with what you can buy at the konbini (there will probably be some in the main station concourse), but eki-ben are a fancier option.

Shinkansen and long-distance trains have on-board toilets.

Rail (train, subway, tramway…)

Trains/subways generally run every 2/3 minutes (especially in cities), so all you have to do is get to the right platform. The exact timetable usually doesn’t matter. However, there are local, express, rapid, rapid express, limited express… trains that skip some of the stops. You shouldn’t worry about this if you’re traveling between two “big” stops (we’ve never had to worry about it, even outside touristy areas, but it’s always good to bear in mind).

Platforms are fixed almost everywhere. Platform x always serves line y in the direction of z. It’s super-easy to get on the train, since you can rely on the track information provided by Google Maps.

Names are written in English everywhere (really everywhere, even deep in mountain villages) and often announced in English (in addition to Japanese, and sometimes Korean and/or Chinese). Station names are always written in “Western” characters as well.

Train tickets can be booked at automatic ticket machines in stations (or directly with staff, but don’t expect to always find someone who speaks English…), with or without the JR pass.

Bus

Most of the time, you get on in the middle and get off at the front.

You either have a special ticket for the day (in some cities only), or a one-way ticket (bought at the station), or you pay with the IC card (when possible, which we’ve mostly seen in Tokyo and the surrounding area), or you take a ticket when you get on the bus at the little machine next to the door.

If you take a ticket in the bus, it has a number on it. Next to the driver, there’s a screen with the numbers and the fare to be paid according to the number on your ticket. When you get off, you just put the ticket and the fare into an automatic machine (the driver doesn’t handle the money). If you need to change money (on a 1000 yen bill), there’s an automatic machine for that right next to the payment machine.

If you have a prepaid ticket (single ride), you insert it into the machine.

If you have a ticket for the day, show it to the driver as you get off.

Language

The legend that Japanese people speak very little English proves to be true. Even in big cities, in places that are very popular with tourists, you can’t rely solely on the hope of running into someone who speaks English!

There are several strategies for getting by: either you learn basic Japanese (it’s great fun, but you need to be motivated), which they’ll be very happy to hear; or you prepare the tools you need to get by (Google Translate is free and can translate text, speech, photos…) and learn to master them before you get there; otherwise, prepare to communicate with a lot of gestures…

The Japanese have a different way of pronouncing English. Learning their way of pronouncing (to understand it and make yourself understood) and learning a few useful words (knowing how to recognize “toilet” or “ramen” in Japanese helps a lot) is a small effort to make for a lot of comfort on the spot!

Manners and wellbehavior

If you don’t want to contribute to the cliché that gaijin (foreigners) are impolite, dirty and a nuisance, here are a few community rules to observe in Japan.

- People line up everywhere. In stations, at bus stops, to order food, to enter a place… queuing areas are often marked on the ground, otherwise you just follow the flow.

- Don’t eat while walking, so you don’t disturb the people walking behind you, but also don’t spill food on the ground (and I must add, because food in Japan is art and we should enjoy it).

There are often places to eat when you buy food on the street, otherwise you have to eat in front of the shop where you bought it (as some people will tell you). The shopkeeper who sold you the food will collect any waste. - There are very few public garbage cans, apart from those for bottles and cans near the vending machines. You don’t throw your garbage in the public toilets, you take it with you and throw it away at home (or give it to the shop where you bought your food). So remember to take a small plastic or tote bag with you so you can collect your garbage.

- On public transport, there are usually places for people with special needs. You can sit there, but the space is freed up as soon as an elderly person, injured person, pregnant person, person with a small child… needs it.

- Don’t talk loudly on public transport, or in public spaces in general (including on the phone). Also don’t listen to music or videos on your phone in the street, and certainly not on public transport.

- You don’t let your umbrella drip inside: at the entrance of various buildings, there’s either a place to leave your umbrellas, or a device to dry your umbrellas, or plastic bags (you put your umbrella in the machine and take it out already wrapped in its plastic bag).

If you don’t want to consume a lot of single-use plastic bags, I’d advise you to collect the first one you use and keep it in a pocket of your backpack. Or if you have a folding umbrella, take the cover with you and use it then to avoid the plastic bag.

Purchases

Cash and cards

Have cash! In one month, having paid for everything we could with a credit card, we needed €1,000 in cash (for 2 people), for visits to the temples and for many restaurants (+ topping up the IC card, ta-q-bin, souvenirs in the temples, snacks…).

You can withdraw cash in konbini (convenience stores) at the best rate. To avoid fees altogether, I advise you to use a Revolut card (which we used for all our card payments, by the way, as it allows you to pay free of charge almost anywhere in the world).

The only time we needed a real credit card was to block a reservation (warranty).

Information about shops

Find out in advance about the stores you want to visit. Stores are scattered (except if you stick to the one main street with chain stores maybe), and many are in basements or on a floor, with unfamiliar logos and names written in Japanese…

If you’re planning to buy something in particular, make a list of the stores you’ll be looking for in advance, by doing a little research on the Internet. Also look for store logos and names written in Japanese characters so you know what to look for. I’ve started a list which you can find at the end of the article!

Stores and restaurants don’t have the same opening hours as they do in other countries, and these can vary greatly from one type of shop/restaurant to another, from one city to another, from one district to another… Find out before you head off on a shopping spree, or if you’re counting on a particular restaurant for lunch.

Tax Free

You can buy Tax Free in Japan (always check your country’s regulations on what you can bring back from abroad). You can do this for as little as 5,500 yen (around €35) tax-free in the same store on the same date (in participating stores). When a store offers Tax Free shopping, it’s usually written in large letters in the window.

To benefit from tax free (i.e. not to pay the 8% tax on food or 10% on other goods), you usually have to go to a special checkout (this will be indicated in the store). Your purchases will be recorded on your passport.

Tax Free consumables (cosmetics, food, etc.) cannot be consumed in Japan: they will be packaged with a seal that you must keep until your departure from Japan. Other products can be unpacked and used in Japan, but you must take them with you when you leave the country.

At the airport, you’ll have to scan your passport at customs (via an automatic terminal), and you’ll get a confirmation message or potentially a message telling you that you have to go through the checkpoint (we didn’t have to go through the checkpoint). You should therefore carry your Tax Free purchases with you after dropping off your hold luggage, or indicate during check-in that you have Tax Free goods in your suitcase before they send it away.

Plastic bags

Plastic bags are now charged, and you’ll usually be asked if you want one (unlike before, when they’d give them to you straight away without giving you time to refuse). Remember to bring a reusable bag or your backpack to avoid taking them.

Fitting rooms

In clothing stores, shoes are removed before entering the booth. If you’re identified as a woman, you’ll be given a cap to put over your head to get through the clothes without putting make-up on them.

Shoes

You’re going to have to take your shoes off quite often, so make sure your shoes are easy to take off without having to sit down, untie your shoes each time, and so on.

You can also pack a tote bag in your backpack to avoid taking the plastic bags you’ll be handed to put your shoes in (or take a plastic bag you already have and reuse it).

Restaurants

We’ve never been charged for anything we’ve had as an extra (not ordered), from green tea to octopus sashimi, miso, amuse bouche… (I’ve you just shouldn’t eat what’s served before you order in izakaya’s, but I wouldn’t know, I didn’t have a single bad experience).

There’s always free water and/or green tea in restaurants, from the small local store to the more upscale eatery. Even at McDonald’s you can ask for a free glass of water! It’s usually served to you spontaneously, but it’s quite common to help yourself too (either there are carafes at the table, or there’s a corner to help yourself).

The food is good, it’s cheap, the portions are big. The rice portions are really big, as are the noodles, so don’t hesitate to ask for a smaller portion whenever possible. Rice is served with almost everything, so you can end up with rice with your bowl of ramen if you’re not careful about the menu you choose.

When it’s sold as “spicy“, it’s really quite spicy by Western standards.

It’s rare to make a reservation for a restaurant (except for the more expensive ones like good sushi or meat restaurants), but it’s not uncommon to queue, which is normal for Japanese people. We avoided it most of the time, but you shouldn’t be surprised to see a line of 20 people in front of a tiny ramen bar that can accommodate 7 at a time. If there’s no queue, you generally sit where you like, although when Westerners arrive, the restaurant staff tend to sit them down (I imagine they’ve had to deal with tourists waiting idly at the entrance so many times that they’re now reacting directly).

Normally you have to call the staff to place an order, but I have the impression that they come spontaneously when they see tourists that have been sitting for a while without ordering anything, out of habit. So don’t hesitate to call the staff when you’re ready to order, it’s not impolite.

Doggy bags don’t exist in Japan.

In many restaurants (especially establishments like ramen bars), people come to eat well, fast and cheap. It’s rude to stay when you’re done and there is a waiting line. This doesn’t mean you have to force yourself to eat fast, but when there’s a line of 10 people waiting to come and swallow their evening meal, you avoid taking out your phone to scroll through Instagram…

You can ask for an apron (pronounced “eh-pu-ron” Japanese-style) in ramen-style restaurants (you’ll see that staining your shirt will happen a lot when eating ramen, and ramen broth is super greasy). This is the kind of restaurant where businessmen go to have their dinner on their way out of the office, while they still have their white shirt on, so the apron is more than necessary!

Hotels

We stayed mainly in 3* hotels (and a few 4*), and I found the prices quite low and the standard quite high compared with 3* hotels back home. The staff are really helpful. Cleanliness is beyond reproach.

There are still hotels with smoking rooms, so check to see if this is the case and if your room is non-smoking. Sometimes smoking and non-smoking rooms are on the same floor, and the smell of cold smoke rooms can be perceived from common areas and other rooms. If this bothers you, I’d advise you to look for a totally non-smoking hotel that looks recent (some hotels have recently started to make their rooms non-smoking, but the smell of cigarettes stays on furniture for a long time…).

All hotels have… pyjamas (2-piece pyjamas, yukata or dressing gown depending on the hotel) and slippers. This is something you can avoid packing in your suitcase, if you’re thin enough. I’m tall and a size L to XL. There’s only one place where I couldn’t wear the pants at all, however the button-down tops were often too tight for my breasts, I wouldn’t dare wandering around the hotel in them.

Many hotels with lots of floors have rooms with windows you can’t open. If you think this will bother you, try to choose lower hotels and/or check with the hotel in advance if they have windows that open (spending a week in a room with only air con is not very pleasant).

“Amenities” (hygiene/cosmetic products and instant coffee) are generally available in self-service on the reception floor. In your room’s bathroom you’ll always have 3 large bottles with shower gel, shampoo and conditioner, but extras will often be available so you can take what you need yourself (this can be coffee/tea/instant drinks, moisturizers, facial cleansers, toothbrush and toothpaste, hairband or elastic band, cotton buds… it varies a lot from hotel to hotel).

You can leave your luggage at the hotel if you arrive too early for check-in, or if you don’t want to take it directly with you after check-out. In some hotels, this is self-service, with an anti-theft cable and a code, while in others it’s the staff who take care of it.

Toilets

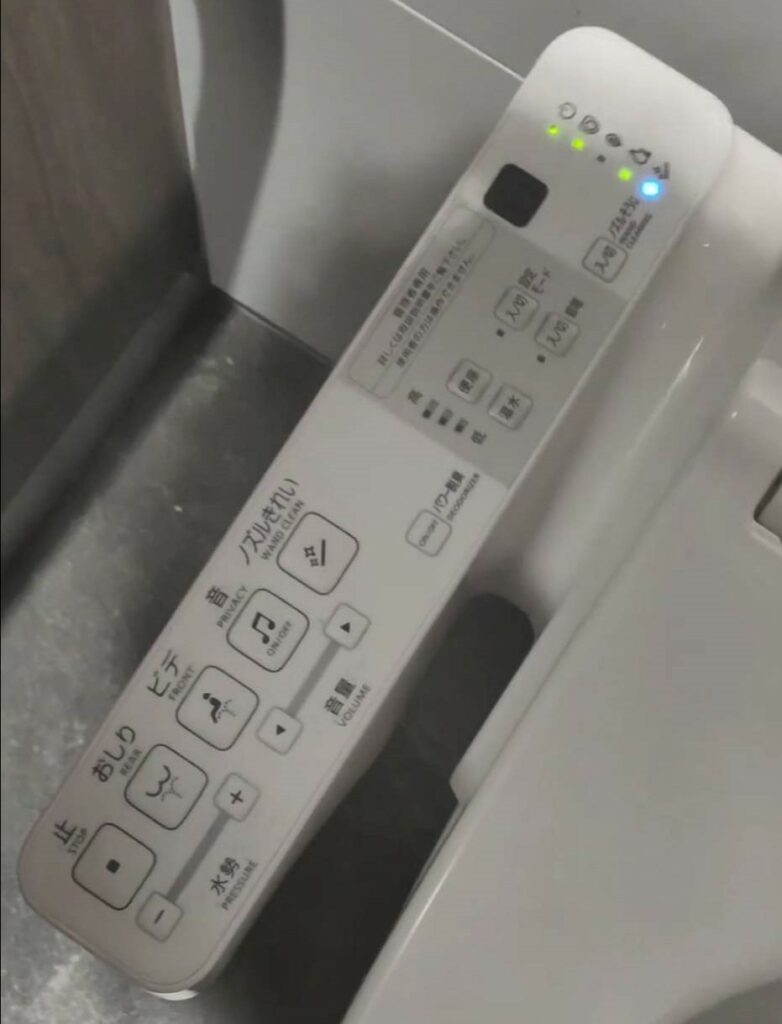

You can’t talk about Japan without writing a paragraph about its toilets!

Many public toilets (and all hotel toilets) have a number of common functions in Japan, such as: heating, jet for rinsing (these are the two must-haves), ambient noise to mask what you’re doing, odor vacuum, buttock dryer, water massage (…), automatic bowl cleaning… The functions are almost always written in English too, with icons (as is often the case in Japan).

The toilet often flushes on its own, or via a non-contact button (you just have to put your hand in front of it), or via a button next to all the buttons mentioned above, or sometimes with a silly up/down button on the side of the bowl. In this case, it’s useful to remember the kanji for small flush: 小 and the kanji for large flush: 大 .

There are public toilets everywhere, whether you’re in town or in the middle of a hike. The buildings are very aesthetically pleasing, so that they blend in with the landscape. On the other hand, it often happens that there are no toilets in restaurants (which is normal, given that there are enough of them in the public space).

There will be some in temples (or just before the entrance), often in coffee shops (at least at Starbucks), in shopping malls, at the start of hikes and at certain stages of the hike, in stations, in shopping streets, on long-distance trains…

There are also traditional Japanese toilets (on the women’s side at least), a kind of urinal built into the floor (but still in an enclosed cubicle). To use them, you have to squat down, facing the pipe system (I confess I haven’t tested it, as I don’t have enough faith in my thigh muscles).

There are quite a few toilets with child seats in the cabin, on both the men’s and women’s sides. These seats allow you to sit a small child in the cabin while you do what you have to do. These cabins will have a logo on the door to indicate this. Changing tables are also often available on both the men’s and women’s sides.

Floors

Japanese floors work in the same way as in the USA: the ground floor is floor 1.

Floors are denoted xF for floor x, and Bx or BxF for floors below the first floor. Example: 1F = first floor (ground floor for Europeans), 5F = 5th floor, B2 = floor -2…

Water

Tap and fountain water is safe to drink, unless otherwise stated.

Trash cans

There aren’t many public garbage cans, apart from those for cans and bottles next to the vending machines. Everyone is responsible for their or her own waste and is expected to take it home. Always carry a small plastic bag to take your garbage back to your hotel or other place of residence.

When you eat in the street, you’re supposed to eat in an eating area or in front of the shop where you bought your food, not while walking (see “Manners”). The person who sold you the food will take back your garbage, or if you’re in an eating area, there will be trash cans there.

In chain restaurants and cafes, you clean your tray yourself. There are garbage cans for sorting different types of waste. For example, you don’t throw a container with liquid in it into the garbage can; there’s a receptacle for the liquid.

Crowds

Not a fan of crowded places? Same for us! If you’re scared about big crowds in Japan, here’s my number one tip: avoid anything you see on Instagram (it turns out disappointing very often anyway if you’re looking for genuine experiences).

If you need quiet places and want to avoid crowds, here are a few tips:

- Choose places based on your interest and search alternatives for famous spots. Public transportation is so good in Japan that you can easily avoid points of interest packed in the same area / in city centers. Honestly, there are so many places more amazing than Tokyo and Kyoto, and even inside those cities there are so many interesting areas that are not Instagram spots!

- Go early or late. When you visit open areas without opening times, try to go as soon as the sun is up. Some places are beautiful and less crowded in the evening.

- Avoid weekends. Generally, weekends are the worst days to visit touristy spots. However, note that many places are still crowded during the week because of school field trips (that’s the case for temples, parks…).

If you know crowds are exhausting to you but really want to visit some of the famous spots, plan for quieter moments and places to take a breath.

Japanese people are super respectful even in crowded places, they’re not the ones who will bump into you or prevent you from moving around, so you’d better visit a place crowded with locals than one visited by foreigners mostly.

A few chain stores and restaurants to look out for

About anything at a low price (bazar stores)

- Don Quijote (very big ones, very famous)

- Daiso

- Can Do (from 100 yen)

Anime/Manga/Geek culture

- Mandarake

- Animate

- Lashinbang

In Tokyo, there are variations of these stores, with some specializing in a particular type of product or target audience.

Second hand

- Bookoff (games, books, mangas, cd/dvd, figures…)

- Modeoff (clothes)

- Hardoff (tech)

- Hobbyoff (probably anything that doesn’t belong in above mentioned categories)

Tech and electronics (Big Buy-like)

- Bic Camera

- Yodobashi

Konbini (convenience stores)

- 7/11 (SevenEleven)

- Lawson

- Family Mart

- Mini Stop

- Daily Yamazaki

- NewDays

Food

- Doutor (coffee shop, “their Starbucks”, even though Starbucks is well present in the country)

- Gogo curry

- Coco curry

- Kura (conveyor belt sushi)

So there you have it, all the peculiarities I noted during my trip. If you still have questions, leave them in the comments so I can answer them and complete the article!